Alice C. Linsley

In ancient Egypt the rule of judges and enforcement by police existed from as early as the Predynastic Period (c. 6000- 3150 BC). The Nile Valley was littered with thousands of small communities in which local elders served as judges.

Later, the Pharaoh was supreme judge as the representative of the High God and his son Horus. The second highest legal authority was the Pharaoh's vizier. In the Book of Genesis, we read that Joseph became Pharaoh's chief steward and his high rank gave him authority to punish crimes.

One of the earliest lawgivers in Egypt was Menes (2930-2900 BC). He administered justice and issued edicts which were designed to improve food production and distribution, guard the rights of ruling families, improve education and enhance knowledge of the natural world through geometry and astronomy. Weinman’s sculpture on the South Wall Frieze of the US Supreme Court building depicts Menes as an early lawgiver.

There are records of an office known as "Judge Commandant of the Police" dating to the Fourth Dynasty (2613-2492 BC).

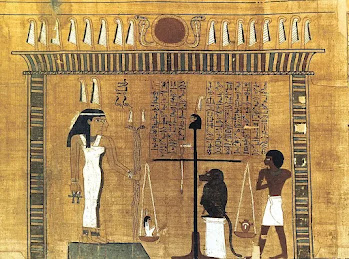

The earliest law codes were of a religious nature and implemented by rulers who were served by royal priests, some of whom were certainly Hebrew. (In Akkadian, the Hebrew ruler-priest caste was called Abrutu, from the Akkadian word abru, meaning priest).The Code of Ani is a negatively worded moral code, like the Ten Commandments. It dates to c. 2500 BC and is contemporaneous with The Reforms of Urukagina (Sumerian, 2500-2350 BC). His reforms are particularly concerned with the governance of the land and rules relating to burials. The text details the role of the king as protector of the weak. However, the Law of Tehut, a nome of Lower Egypt, dates to about 500 years earlier.

Those who broke a taboo by using something they are not to use or touch or by speaking words that they are not to speak, were punished by imprisonment, publicly shamed, or banished. Muttering incantations against the king or blaspheming the throne was a serious offense. The Code of Ani specifically mentions this: "I have not worked witchcraft against the King."

The Pharaoh had the same spiritual and legal authority in his Kingdom as the High Priest had in ancient Israel. Innocent parties were to remain in the city of refuge until the death of the High Priest, at which time the party could return to his people, and he was not to be harmed by any act of retribution.

If a fugitive died in a city of refuge before the High Priest died, he was buried in the city of refuge. His body could be moved for reburial only after the high priest died. This suggests that the legal precedent for treatment of fugitives in the cities of refuge predates Moses. Moses returned to Egypt after the Pharaoh died (Exodus 4:19).

The most serious crimes were those against the throne: robbing royal graves, insurrection, and hiding political enemies. The punishment for robbing grave goods and selling them was impalement, followed by dismemberment. Insurrectionists were sometimes fed to the crocodiles, which would result in the second death since the body and the soul could not be reunited in the afterlife. A royal decree dating to the First Intermediate Period (c.2170–2008 BC) and designed to protect a high-ranking official’s tomb, states, “As for anyone in this entire land who may do an injurious or evil thing to your statues . . . my majesty does not permit that their property nor that of their fathers remain with them, nor that they join their spirits in the necropolis, nor that they remain among the living.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Your comments are welcome. Please stay on topic and provide examples to support your point.